Anarchist Odyssey of the Federalist Papers, Part 3

Download a PDF version of this article.

By: Matt K. [social title=”” subtitle=”” link=”endtheterrorwar.tumblr.com” icon=”fa-tumblr”]

October 3rd, 2015

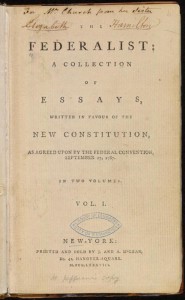

Welcome to the third chapter on my anarchist odyssey of the Federalist Papers. In part 1, the following subjects were tackled by Alexander Hamilton, John Jay, and James Madison: Arguments for a Constitution (No. 1), dangers of ‘foreign’ influence (No. 2-5), dissent between States (No. 6-7), consequence of hostilities between States (No. 8), The Union as a safeguard against factions and insurrection (No. 9-10). In part 2, Hamilton and Madison covered the following: The Union and Navy (No. 11), Union and taxation (No. 12), Union advantages vis a vis economy in government (No. 13), answers to objections on the proposed Constitution (No. 14), Whether the Confederacy can ‘preserve the Union’ (No. 15-20). Anyone wanting a read of the Papers themselves can get a copy here. In the following Mr. Hamilton will be speaking of defects of the Confederation (No. 21-22), necessity of government to ‘preserve the Union’ (No. 23), powers to arbitrate common defense (No. 24-25), the role of restrained legislature on common defense (No. 26-28), militia (No. 29), and general power of taxation (No. 30). As always, I will examining and responding accordingly to the words of the Federalists themselves, from my own perspective. Thus far, none of the authors of the Papers have provided convincing claims for the “necessary evil of government” to the author of this article series himself.

Welcome to the third chapter on my anarchist odyssey of the Federalist Papers. In part 1, the following subjects were tackled by Alexander Hamilton, John Jay, and James Madison: Arguments for a Constitution (No. 1), dangers of ‘foreign’ influence (No. 2-5), dissent between States (No. 6-7), consequence of hostilities between States (No. 8), The Union as a safeguard against factions and insurrection (No. 9-10). In part 2, Hamilton and Madison covered the following: The Union and Navy (No. 11), Union and taxation (No. 12), Union advantages vis a vis economy in government (No. 13), answers to objections on the proposed Constitution (No. 14), Whether the Confederacy can ‘preserve the Union’ (No. 15-20). Anyone wanting a read of the Papers themselves can get a copy here. In the following Mr. Hamilton will be speaking of defects of the Confederation (No. 21-22), necessity of government to ‘preserve the Union’ (No. 23), powers to arbitrate common defense (No. 24-25), the role of restrained legislature on common defense (No. 26-28), militia (No. 29), and general power of taxation (No. 30). As always, I will examining and responding accordingly to the words of the Federalists themselves, from my own perspective. Thus far, none of the authors of the Papers have provided convincing claims for the “necessary evil of government” to the author of this article series himself.

So far, from my experience in reading the previous Federalist Papers, I can make the following determinations of the Federalist authors:

- Hamilton likes to beguile his readers like a modern day politician, he wants you within the Federalists’ good graces, never mind his unprincipled desires to forcibly implement government and a Constitution on those who never wanted either in the first place.

- Jay is at least an honest contender in comparison, he’s made no attempts to deceive with lofty rhetoric in the same manner as Hamilton. Corrupt as they come, and willing to show it.

- Madison appears to reflect himself on Hamilton’s arguments for the Federalist Constitution and Federalist positions, so far, have little to show for his own independent thoughts.

Slow going as my progress on this series may be, these results are incurring some very negative consequences for anybody wanting to “restore the Republic.” Government won’t be less intrusive, less violent, or less dangerous overall even if Americans somehow managed to keep it in its paper cage. By its very nature, its survival depends upon the suffering of others – foreign or domestic. You CANNOT reason with a power hungry institution, much less make it appear preferable towards someone who would like a world without any such institutions. Including a “world government“. So far, I’ve read nothing convincing by the Federalist Papers.

Federalist No. 21, Hamilton:

- “The United States, as now composed, have no powers to exact obedience, or punish disobedience to their resolutions, either by pecuniary mulcts, by a suspension or divestiture of privileges, or by any other constitutional mode. There is no express delegation of authority to them to use force against delinquent members; and if such a right should be ascribed to the federal head, as resulting from the nature of the social compact between the States, it must be by inference and construction, in the face of that part of the second article, by which it is declared, ‘that each State shall retain every power, jurisdiction, and right, not expressly delegated to the United States in Congress assembled.’”

Continuing where we left off at No. 20, Hamilton starts us off by saying that one of the defects of the Confederation is that not enough ‘Constitutional’ power is being granted to a federal authority. He’s literally pleading for a power-grab, presently unforeseeable at the time of writing. The much later Massachusetts Compromise, will see to it that the Federalist’s desired Constitutional powerhouse will be conceded by the Anti-Federalists in a “take this or nothing” scenario. This proves just how supposedly “small government” the Federalist’s position actually were.

- “Who can predict what effect a despotism, established in Massachusetts, would have upon the liberties of New Hampshire or Rhode Island, of Connecticut or New York?”

Had the country been founded on peaceful anarchistic principles, instead of slave-driving warmongers, thieves and rapists such questions would’ve been moot. Obviously the question of how a Stateless society chooses to handle such contrivances is room for discussion and debate, but without any forms of centralized power, there would be no concerns regarding corruption of political office holders or dirty backroom deals, today rightfully categorized as scandals. Notice how Hamilton sidesteps the question of despotism within the federal government that he wants to impose upon the country’s populace, as indicated in No. 1.

- “The peace of society and the stability of government depend absolutely on the efficacy of the precautions adopted on this head.”

There’s a joke for you: A peaceful society and “stability” of an extortion racket on the governed hinge upon each other.

- “The principle of regulating the contributions of the States to the common treasury by quotas is another fundamental error in the Confederation.”

Why should there be a “common treasury” in the hands of the federal government? Decentralized currency, unfortunately criminalized due to its “unregulated” nature by the government, would eventually lead us right into the Jekyll Island cabal that formed the Federal Reserve. Thanks government, for securing monetary monopolies for the benefit of the ruling few. So because the federal government is owned, rigged, and manipulated for a certain “class” of folks (In part 1 I’ve already examined the aristocratic behavior of the Federalists scratching each other’s backs in the forming of the “new Constitution” and “new government”), and therefore they quite easily “represent” themselves and nobody else in this country, we can all marvel at the efficacy of why having governments in the first place is a really terrible notion.

- “The wealth of nations depends upon an infinite variety of causes. Situation, soil, climate, the nature of the productions, the nature of the government, the genius of the citizens, the degree of information they possess, the state of commerce, of arts, of industry, these circumstances and many more, too complex, minute, or adventitious to admit of a particular specification, occasion differences hardly conceivable in the relative opulence and riches of different countries. The consequence clearly is that there can be no common measure of national wealth, and, of course, no general or stationary rule by which the ability of a state to pay taxes can be determined. The attempt, therefore, to regulate the contributions of the members of a confederacy by any such rule, cannot fail to be productive of glaring inequality and extreme oppression.”

The implication I get from Hamilton’s wording above is that “without centralized taxation, the nation is doomed to fail!” This is far from a rational assessment of a situation at any given time. I’d ask readers to skip over where he mentions “the nature of the government” for a moment. No government. Without government we can dismiss the State taxation levied on the “governed” as well. What are we left with? We still have soil, climate, production, a citizenry of geniuses, and various means of commerce. If you ask me, that scenario sounds pleasant, rather than the alternative presented by the Federalists. If Hamilton wasn’t pushing for national governance to subjugate the “governed”, he’d sound like a raving lunatic on the street corner otherwise. Nobody would, or should, hold the Federalists in “sinless” deified historic disregard.

- “There is no method of steering clear of this inconvenience, but by authorizing the national government to raise its own revenues in its own way. Imposts, excises, and, in general, all duties upon articles of consumption, may be compared to a fluid, which will, in time, find its level with the means of paying them.”

So let me get this straight: The Confederate model didn’t work, therefore the Federalist’s in its place, sought to impose its own taxation authority to supposedly ‘resolve’ the issue. If you prefer to be robbed blind by a federal tax collector instead of a confederate tax collector, it’s no business of mine to criticize you’re personal preferences. However, I will call it what it is: You’re still being robbed of your means of making money. Good luck with that.

- “If inequalities should arise in some States from duties on particular objects, these will, in all probability, be counterbalanced by proportional inequalities in other States, from the duties on other objects. In the course of time and things, an equilibrium, as far as it is attainable in so complicated a subject, will be established everywhere.”

That’s quite the reformist dream there Mr. Hamilton. With the right equation of (Federalist-endorsed) robbery, there will be some sort of happy equilibrium, and nothing will ever go wrong because the robbery is equally distributed across the geographic landmass of the States. There’s a reason tax rebellion was infamous in early America, foolish narratives like the one presented above. He doesn’t even pause to question the moral nature of imposing the so-called “equilibrium” on the governed citizens of the States, just spins an all-too-suspiciously-happy tale of prosperity through robbery through a Federalist monopoly on violence.

- “In every country it is a herculean task to obtain a valuation of the land; in a country imperfectly settled and progressive in improvement, the difficulties are increased almost to impracticability. The expense of an accurate valuation is, in all situations, a formidable objection. In a branch of taxation where no limits to the discretion of the government are to be found in the nature of things, the establishment of a fixed rule, not incompatible with the end, may be attended with fewer inconveniences than to leave that discretion altogether at large.”

I hope readers of this series are catching onto Hamilton’s game. Between the previous quotation and this one, he’s changed his position from “radical Federalist seeking to impose equal-opportunity robbery across the States” to “moderate, neutral party reflecting on the subject of taxation” above. Astounding. Here’s a simple task: No government, no taxation.

Federalist No. 22, Hamilton:

- “It is indeed evident, on the most superficial view, that there is no object, either as it respects the interests of trade or finance, that more strongly demands a federal superintendence.”

Noted: Federalist’s believe in federal oversight regarding trade and finances.

- “The interfering and unneighborly regulations of some States, contrary to the true spirit of the Union, have, in different instances, given just cause of umbrage and complaint to others, and it is to be feared that examples of this nature, if not restrained by a national control, would be multiplied and extended till they became not less serious sources of animosity and discord than injurious impediments to the intercourse between the different parts of the Confederacy.”

So the States within the confederacy aren’t allowed to have regulatory measures, only the Union can. The Union can do no wrong, ever.

- “The power of raising armies, by the most obvious construction of the articles of the Confederation, is merely a power of making requisitions upon the States for quotas of men.”

Okay, so having quotas of men for armed infantry is a no-no according to Mr. Hamilton. However, and here’s the kicker, having an unlimited supply of “Militias of the States” (Article 1, Sec. 8 of the U.S. Constitution) is totally fine. Double standards? I think so.

- “The system of quotas and requisitions, whether it be applied to men or money, is, in every view, a system of imbecility in the Union, and of inequality and injustice among the members.”

There’s the rub. The Federalist’s have no problem counting the problems of Statism within the Confederacy, but they never look in the mirror.

- “Every idea of proportion and every rule of fair representation conspire to condemn a principle, which gives to Rhode Island an equal weight in the scale of power with Massachusetts, or Connecticut, or New York; and to Delaware an equal voice in the national deliberations with Pennsylvania, or Virginia, or North Carolina.”

There would be no concerns for “fair representation” on behalf of any governance in an anarchist climate. Having no self-proclaimed rulers, by individuality or plurality that call themselves “Rhode Island” (or any other State listed above by Hamilton) would be an issue. If there’s one thing the indigenous have had correctly from the beginning, tribal warfare with each other aside, it’s the acknowledgment that these arbitrary boundaries enforced by the violent monopoly that calls itself the “United States” is an untrustworthy mass guided by a centralized federal authority who broke treaties with said tribes.

- “It may be objected to this, that not seven but nine States, or two thirds of the whole number, must consent to the most important resolutions; and it may be thence inferred that nine States would always comprehend a majority of the Union. But this does not obviate the impropriety of an equal vote between States of the most unequal dimensions and populousness; nor is the inference accurate in point of fact; for we can enumerate nine States which contain less than a majority of the people; and it is constitutionally possible that these nine may give the vote.”

I could honestly care less for the voting prowess of individual State governments, and I certainly deplore the conspiratorial nature from which they agreed to make up the ‘Constitutional’ embodiment of so-called ‘representatives’ via the Senate and Congress of the U.S. government. Why don’t I care? Perhaps because I don’t wish to impose a monopoly on violence towards others, much less myself. No amount of voting, in whatever form, is going to change that.

- “Congress, from the nonattendance of a few States, have been frequently in the situation of a Polish diet, where a single vote has been sufficient to put a stop to all their movements. A sixtieth part of the Union, which is about the proportion of Delaware and Rhode Island, has several times been able to oppose an entire bar to its operations. This is one of those refinements which, in practice, has an effect the reverse of what is expected from it in theory. The necessity of unanimity in public bodies, or of something approaching towards it, has been founded upon a supposition that it would contribute to security. But its real operation is to embarrass the administration, to destroy the energy of the government, and to substitute the pleasure, caprice, or artifices of an insignificant, turbulent, or corrupt junto, to the regular deliberations and decisions of a respectable majority.”

Well, that’s encouraging. Voting powers of a single State government, is supposed to “destroy the energy of the government.” There must never be a clause for abolishment of government altogether though, that’d be asking too much.

- “It is often, by the impracticability of obtaining the concurrence of the necessary number of votes, kept in a state of inaction. Its situation must always savor of weakness, sometimes border upon anarchy.”

Before the above sentence, Hamilton lists ‘delays, negotiation and intrigue, and promises of the public good’ as tactics that favor the voting mechanism provided by the several States. I’m fairly certain, in this context, anarchy doesn’t mean an implication of desirable Statelessness.

- “One of the weak sides of republics, among their numerous advantages, is that they afford too easy an inlet to foreign corruption.”

For all the cries of “returning America into the Constitutional Republic” commonplace today, it’s a bit ironic that at least the Federalist Alexander Hamilton could identify weaknesses even in his proposed government to the audiences of the Federalist Papers he’d written. In all my understanding of American history, I’ve seen no evidence wherein the country faced a serious decline in domestic political corruption for foreign influences to seep in and gain a sweet monopoly on local, state or Federal government. In short, our country has never required external assistance in the department of internal corruption.

- “In republics, persons elevated from the mass of the community, by the suffrages of their fellow-citizens, to stations of great pre-eminence and power, may find compensations for betraying their trust, which, to any but minds animated and guided by superior virtue, may appear to exceed the proportion of interest they have in the common stock, and to overbalance the obligations of duty.”

Hence why I take certain issue with anybody claiming to be my “representative.” If I could advise my fellow Americans, I’d ask them to be equally cautious. Instead of providing unquestioning cheerleading to holders of political offices throughout the country. There are absolutely NO exceptions to the rule, as evidenced by Shane’s Adventure’s in Illinois Law anthology.

- “The Earl of Chesterfield (if my memory serves me right), in a letter to his court, intimates that his success in an important negotiation must depend on his obtaining a major’s commission for one of those deputies. And in Sweden the parties were alternately bought by France and England in so barefaced and notorious a manner that it excited universal disgust in the nation, and was a principal cause that the most limited monarch in Europe, in a single day, without tumult, violence, or opposition, became one of the most absolute and uncontrolled.”

Imagine how much less problematic these issues would’ve been with anarchists rejecting the supposed “authorities” of the Earl, Sweden, France, and England’s governing entities. Abolishment would be doing a huge favor.

- “A circumstance which crowns the defects of the Confederation remains yet to be mentioned, the want of a judiciary power. Laws are a dead letter without courts to expound and define their true meaning and operation. The treaties of the United States, to have any force at all, must be considered as part of the law of the land. Their true import, as far as respects individuals, must, like all other laws, be ascertained by judicial determinations. To produce uniformity in these determinations, they ought to be submitted, in the last resort, to one supreme tribunal. And this tribunal ought to be instituted under the same authority which forms the treaties themselves.”

Here we have, I believe, the first evidence within the Federalist Papers of an author calling for a judicial monopoly. And we wonder to ourselves when things went belly-up in this country. How about at the very bloody start?

- “The treaties of the United States, under the present Constitution, are liable to the infractions of thirteen different legislatures, and as many different courts of final jurisdiction, acting under the authority of those legislatures. The faith, the reputation, the peace of the whole Union, are thus continually at the mercy of the prejudices, the passions, and the interests of every member of which it is composed. Is it possible that foreign nations can either respect or confide in such a government? Is it possible that the people of America will longer consent to trust their honor, their happiness, their safety, on so precarious a foundation?”

I certainly don’t share Hamilton’s faith in the “new government” and “new Constitution” he had presented since the very first Federalist Paper.

- “A single assembly may be a proper receptacle of those slender, or rather fettered, authorities, which have been heretofore delegated to the federal head; but it would be inconsistent with all the principles of good government, to entrust it with those additional powers which, even the moderate and more rational adversaries of the proposed Constitution admit, ought to reside in the United States.”

There is no such thing as a “good government.”

- “We should create in reality that very tyranny which the adversaries of the new Constitution either are, or affect to be, solicitous to avert.”

Collectivist “we” aside, Hamilton and his conspirators had certainly worked to impose tyranny of the “new Constitution.” For once, he hasn’t lied or used unconvincing beguiling political rhetoric to support his Federalist position.

- “The fabric of American empire ought to rest on the solid basis of the consent of the people. The streams of national power ought to flow immediately from that pure, original fountain of all legitimate authority.”

Well, it’s nice to see that Hamilton finishes this Paper off with some blatant honesty on America’s status as an empire. Ask any average American today if they think so, and you’re allegiance to the monopoly on violence will be put into question and you may even be publicly ostracized as being “un-American”. In Federalist No. 1, Hamilton says, and I quote: ‘After an unequivocal experience of the inefficacy of the subsisting federal government, you are called upon to deliberate on a new Constitution for the United States of America.’ A sense of obligatory creation of a “new government” and “new Constitution” are presented from the very start. Here, however, he speaks of Americans having a sense of “consent” by which the legitimate authority of the Federalist’s government will function.

Let me run that by you again: Hamilton coercively implies that a new monopoly on violence (government) MUST be formed and alongside it will be a paper cage (Constitution), giving his audience no other choices. Now Hamilton makes the case that ONLY ‘consent of the people’ will provide the means for the Federalist’s government to be recognized as a legitimate authority. ‘Consent of the governed’, for whatever its worth, wasn’t even considered in Federalist No. 1. That shows you just how much the early aristocracy compassionately displayed the manner of a ‘social contract’ to the general populous of the governed at the time. In the words of George Carlin:

“They don’t care about you at all..at all..AT ALL. And nobody seems to notice. Nobody seems to care. That’s what the owners count on. The fact that Americans will probably remain willfully ignorant of the big red, white and blue dick that’s being jammed up their assholes every day, because the owners of this country know the truth. It’s called the American Dream, because you have to be asleep to believe it.”

Federalist No. 23, Hamilton:

- “The Necessity of a Government as Energetic as the One Proposed to the Preservation of the Union.”

That’s the title of No. 23, we’re off to another ugly start with Mr. Hamilton and company.

- “The circumstances that endanger the safety of nations are infinite, and for this reason no constitutional shackles can wisely be imposed on the power to which the care of it is committed.”

I say paper cage, Hamilton says Constitutional shackles. Before this sentence he speaks of ‘unlimited powers of common defense.’ It only gets worse, as I’ve noted before very few decent caveats found throughout the Papers.

- “We must extend the laws of the federal government to the individual citizens of America; we must discard the fallacious scheme of quotas and requisitions, as equally impracticable and unjust. The result from all this is that the Union ought to be invested with full power to levy troops; to build and equip fleets; and to raise the revenues which will be required for the formation and support of an army and navy, in the customary and ordinary modes practiced in other governments.”

Hamilton’s previous use of the word “MUST” leaves much discontent to be gathered from the above passage. I can only ponder how many lives were destroyed by defiant Americans who didn’t wish to be forcibly employed into the arms of the federal government under the pretexts of ‘common defense and general welfare.’ The word “must”, in this context, not unlike its previous citations in the Papers, reads like a violent expectation of a robber baron that calls itself ‘government’ and demands your unquestioning servitude.

- “The government of the Union must be empowered to pass all laws, and to make all regulations which have relation to them. The same must be the case in respect to commerce, and to every other matter to which its jurisdiction is permitted to extend.”

Read: The Federalist’s really enjoy power-grabs, whether opponents agree with them or not.

- “Who is likely to make suitable provisions for the public defense, as that body to which the guardianship of the public safety is confided; which, as the centre of information, will best understand the extent and urgency of the dangers that threaten; as the representative of the whole, will feel itself most deeply interested in the preservation of every part; which, from the responsibility implied in the duty assigned to it, will be most sensibly impressed with the necessity of proper exertions; and which, by the extension of its authority throughout the States, can alone establish uniformity and concert in the plans and measures by which the common safety is to be secured? Is there not a manifest inconsistency in devolving upon the federal government the care of the general defense, and leaving in the State governments the effective powers by which it is to be provided for?”

Hamilton is one who provides a threat of force behind his “must” statements. This leaves me questioning at precisely what cost to the liberties of the governed had he sought to impose the so-called ‘public safety.’

- “A government, the constitution of which renders it unfit to be trusted with all the powers which a free people ought to delegate to any government, would be an unsafe and improper depositary of the national interests.”

I don’t see what use free people need for ANY government.

- “The powers are not too extensive for the objects of federal administration, or, in other words, for the management of our national interests; nor can any satisfactory argument be framed to show that they are chargeable with such an excess.”

Ah, collectivist “national interests.” Hamilton believes the federal government can NEVER be over-extensive in its power. I wonder how many readers of this series agree with such notions.

- “If we embrace the tenets of those who oppose the adoption of the proposed Constitution, as the standard of our political creed, we cannot fail to verify the gloomy doctrines which predict the impracticability of a national system pervading entire limits of the present Confederacy.”

Since I don’t recognize the governing authorities of either the Union or Confederacy, nothing is practical about Statism in general.

Federalist No. 24, Hamilton:

- “To the powers proposed to be conferred upon the federal government, in respect to the creation and direction of the national forces, I have met with but one specific objection, which, if I understand it right, is this, that proper provision has not been made against the existence of standing armies in time of peace; an objection which, I shall now endeavor to show, rests on weak and unsubstantial foundations.”

This is going to be good. And by that I mean, very disturbing.

- “The whole power of raising armies was lodged in the legislature, not in the executive; that this legislature was to be a popular body, consisting of the representatives of the people periodically elected; and that instead of the provision he had supposed in favor of standing armies, there was to be found, in respect to this object, an important qualification even of the legislative discretion, in that clause which forbids the appropriation of money for the support of an army for any longer period than two years a precaution which, upon a nearer view of it, will appear to be a great and real security against the keeping up of troops without evident necessity.”

Anyone worth their weight in consistency for themselves would see that Hamilton’s argument hinges upon the notion of legislative “representation.” That’s dangerous within itself for its own separate reasons.

- “It must needs be that this people, so jealous of their liberties, have, in all the preceding models of the constitutions which they have established, inserted the most precise and rigid precautions on this point, the omission of which, in the new plan, has given birth to all this apprehension and clamor.”

Hamilton is arguing that the Federalist’s recognize that the governed are concerned for their liberties. That still leaves us with the questionable nature of Article 1, Sec. 8. Clause 15 of the Constitution they sought to impose in place of the Articles of Confederation. Government loves you so much, they’ll call you “insurrectionist” for seeking to abolish them without resorting to reformist attempts at “changing the system from within.” Because, violence is fun.

Article 6 states:

“No State, without the consent of the United States in Congress assembled, shall send any embassy to, or receive any embassy from, or enter into any conference, agreement, alliance or treaty with any King, Prince or State; nor shall any person holding any office of profit or trust under the United States, or any of them, accept any present, emolument, office or title of any kind whatever from any King, Prince or foreign State; nor shall the United States in Congress assembled, or any of them, grant any title of nobility. No two or more States shall enter into any treaty, confederation or alliance whatever between them, without the consent of the United States in Congress assembled, specifying accurately the purposes for which the same is to be entered into, and how long it shall continue. No State shall lay any imposts or duties, which may interfere with any stipulations in treaties, entered into by the United States in Congress assembled, with any King, Prince or State, in pursuance of any treaties already proposed by Congress, to the courts of France and Spain. No vessel of war shall be kept up in time of peace by any State, except such number only, as shall be deemed necessary by the United States in Congress assembled, for the defense of such State, or its trade; nor shall any body of forces be kept up by any State in time of peace, except such number only, as in the judgement of the United States in Congress assembled, shall be deemed requisite to garrison the forts necessary for the defense of such State; but every State shall always keep up a well-regulated and disciplined militia, sufficiently armed and accoutered, and shall provide and constantly have ready for use, in public stores, a due number of filed pieces and tents, and a proper quantity of arms, ammunition and camp equipage. No State shall engage in any war without the consent of the United States in Congress assembled, unless such State be actually invaded by enemies, or shall have received certain advice of a resolution being formed by some nation of Indians to invade such State, and the danger is so imminent as not to admit of a delay till the United States in Congress assembled can be consulted; nor shall any State grant commissions to any ships or vessels of war, nor letters of marque or reprisal, except it be after a declaration of war by the United States in Congress assembled, and then only against the Kingdom or State and the subjects thereof, against which war has been so declared, and under such regulations as shall be established by the United States in Congress assembled, unless such State be infested by pirates, in which case vessels of war may be fitted out for that occasion, and kept so long as the danger shall continue, or until the United States in Congress assembled shall determine otherwise.” (Author’s note: Neither “insurrection” or “rebellion” were found in the source of the Articles of Confederation I’ve found, that’s a significant change from the Federalist’s Constitution folks love fawning themselves over).

Note the absence of accusatory “insurrection” upon the governed. You can thank the Federalist’s for that modified addition, if you so desire. In short, there’s no reason to take Hamilton on his word that the government he proposed through the Papers gives any semblance of recognition to people concerned about the status of their freedom. As I see it, the very presence of ANY government violates freedom.

- “Pennsylvania and North Carolina are the two which contain the interdiction in these words: ‘As standing armies in time of peace are dangerous to liberty, they ought not to be kept up.’ This is, in truth, rather a caution than a prohibition. New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Delaware, and Maryland have, in each of their bills of rights, a clause to this effect: ‘Standing armies are dangerous to liberty, and ought not to be raised or kept up without the consent of the legislature’; which is a formal admission of the authority of the Legislature. New York has no bills of rights, and her constitution says not a word about the matter. No bills of rights appear annexed to the constitutions of the other States, except the foregoing, and their constitutions are equally silent. I am told, however that one or two States have bills of rights which do not appear in this collection; but that those also recognize the right of the legislative authority in this respect.”

I can certainly see the reasoning why standing armies are considered dangerous to freedom. However, this is no consolidation with regards to the Federalist’s “Constitutional” implementation of a government and armed forces joined at the hip. That’s precisely the exact model we live under today, and have for the last several centuries of the country’s existence.

To make my case, I’ve prepared the following citations:

- Continental Army served George Washington.

- Continental Navy served Abraham Whipple.

- Continental Marines served George Washington.

- S. Army & U.S. Air Force serve under Sec. of War as a member of the President’s Cabinet.

- S. Army serves under Sec. of Army who answer to the President through the Sec. of Defense.

- S. Marine Corps serves under Sec. of Navy who answers to the President as a member of the Cabinet.

- S. Navy serves under Sec. of Navy who answers to the President.

- S. Air Force serves under Sec. of Air Force who answers to the President.

- S. Coast Guard has switched hierarchical places between Treasury Department (1915-1917), the Navy Department (1917-1919), Department of the Treasury (1919-1946), Navy Department (1941-1946), Department of Treasury (1946-1967), Department of Transportation (1967-2003), and finally currently resides with the Department of Homeland Insecurity (2003-present).

- Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff answers to the President.

- Joint Special Operations Command serves the Department of Defense, who answers to the President.

- Lastly, the Central Intelligence Agency’s General Counsel answers to the President, once approved by the Senate.

In all of America’s five centuries of existence, there has been ‘civil unrest’ which has frequently been met by martial law. The Suspension Clause (Article 1, Sec. 9, Clause 1) expects a constantly unrebellious citizenry of “governed”, or else, “public safety” (national security?) is invoked as the du jour pretext for suspensions of habeas corpus within The States. That’s not a very comforting prospect once you reflect on it, but it’s within the Federalist’s own Constitution they sought to impose on Americans, and unfortunately, they got their wish. Just because something is within the paper cage of 1787, DOES NOT make it moral. To make matters worse, America has been under several “States of Emergency“, leaving plenty of room for expansion of militarized police, perhaps in a last-ditch effort by the State before fully implementing armed forces against Americans themselves as a standing army. With or without an official declaration of a standing army within The States, there’s plenty historic precedence for these abuses of power. This is just one of the many facets of the monstrosity of Statism I warned about in my article, “Anarchist Axioms Against Electioneering.” The Constitution is NOT some sort of holy writ, where even in the unlikely event that it’s appropriately trashed, a similarly dangerous text is defaulted to take its place and continue the cycle of American’s oppressing themselves. There’s NOTHING good to be taken from replacing one unnecessary evil with a younger new version. “Consent of the legislature” be damned, all that means is a legislative entity corrupt enough will gleefully permit standing armies within their respective State’s jurisdiction’s without a second thought. That’s remarkably dangerous, and the legislative powers of the federal government are no less fatal either.

There’s so much wrong with the above quotation, I believe it’s best to move forward before I’m indefinitely detaining myself on this portion of No. 24 due to the dangerous mythologies of the “good Federalists”.

- “Though a wide ocean separates the United States from Europe, yet there are various considerations that warn us against an excess of confidence or security.”

That’s a fairly decent start of a paragraph if I’ve ever seen one. I’d go further and question what is meant by “security.” For whom does it actually apply?

- “These garrisons must either be furnished by occasional detachments from the militia, or by permanent corps in the pay of the government. The first is impracticable; and if practicable, would be pernicious. The militia would not long, if at all, submit to be dragged from their occupations and families to perform that most disagreeable duty in times of profound peace. And if they could be prevailed upon or compelled to do it, the increased expense of a frequent rotation of service, and the loss of labor and disconcertion of the industrious pursuits of individuals, would form conclusive objections to the scheme. It would be as burdensome and injurious to the public as ruinous to private citizens. The latter resource of permanent corps in the pay of the government amounts to a standing army in time of peace; a small one, indeed, but not the less real for being small. Here is a simple view of the subject, that shows us at once the impropriety of a constitutional interdiction of such establishments, and the necessity of leaving the matter to the discretion and prudence of the legislature.”

I don’t wish to repeat myself here, but I guess it’s required: Hamilton’s argument hinges upon the reliability of the legislative authorities NOT being corrupted. I personally don’t have that much faith in any governments, separation of powers in practice or not. Besides, rather than prohibiting expansion of a fourth branch, the Legislative, Executive, and Judicial welcomed Administrative with open arms. There’s your fictitious ‘checks and balances’ at work, readers.

- “If we mean to be a commercial people, or even to be secure on our Atlantic side, we must endeavor, as soon as possible, to have a navy.”

And here we have a self-fulfilled prophecy.

Federalist No. 25, Hamilton:

- “We must expose our property and liberty to the mercy of foreign invaders, and invite them by our weakness to seize the naked and defenseless prey, because we are afraid that rulers, created by our choice, dependent on our will, might endanger that liberty, by an abuse of the means necessary to its preservation.”

It hasn’t proven to be a good sign when Hamilton suggests something “MUST” occur.

- “The American militia, in the course of the late war, have, by their valor on numerous occasions, erected eternal monuments to their fame; but the bravest of them feel and know that the liberty of their country could not have been established by their efforts alone, however great and valuable they were. War, like most other things, is a science to be acquired and perfected by diligence, by perseverance, by time, and by practice.”

There is no liberty to be had with the likes of the Federalists national government.

- “The conduct of Massachusetts affords a lesson on the same subject, though on different ground. That State (without waiting for the sanction of Congress, as the articles of the Confederation require) was compelled to raise troops to quell a domestic insurrection, and still keeps a corps in pay to prevent a revival of the spirit of revolt.”

There’s an amazing amount of hypocrisy on Hamilton’s part regarding the subject of ‘insurrection.’ Member States of the Article of Confederation are criticized for exercising their own domestic standing armies, HOWEVER, under the Union, because the States are conjoined with the Federalist government (Article 1, Sec. 8, Clause 15), how they choose to respond to the subject of ‘insurrection’ isn’t worth equal critique in Hamilton’s view. We must keep in mind that Hamilton is appealing to the expectation that the governed are OBLIGATED to form a “new government” and “new constitution” because that’s what the Federalist’s expect. That isn’t freedom, its blatant coercion from the very start of the Papers.

- “It also teaches us, in its application to the United States, how little the rights of a feeble government are likely to be respected, even by its own constituents. And it teaches us, in addition to the rest, how unequal parchment provisions are to a struggle with public necessity.”

Obviously Hamilton and the other Federalists didn’t take the lesson learned from Massachusetts providing a standing army to handle so-called ‘insurrection’ at heart. If the lesson is that the Massachusetts’s government was in the wrong (which I will not dispute), then obviously the Federalist’s didn’t seek to apply the same educational experience must be handled with regards to the nature of their very own Federalist government.

- “Wise politicians will be cautious about fettering the government with restrictions that cannot be observed, because they know that every breach of the fundamental laws, though dictated by necessity, impairs that sacred reverence which ought to be maintained in the breast of rulers towards the constitution of a country, and forms a precedent for other breaches where the same plea of necessity does not exist at all, or is less urgent and palpable.”

Interesting words to leave off this Paper with. At least Hamilton acknowledges the presence of a ruling entity, instead of playing pretend that he’s a “commoner” while seeking or holding political office. Monarchism was quite a trending thought among the Federalists, and that provides little confidence in the political means. The mentioning of “laws dictated by necessity” aren’t very clear whether he’s pushing for mala in se or mala prohibita legislative abuses towards the governed.

In the words of my colleague Kyle Rearden:

“In the effort to form civil government, especially through the ratification of the federal Constitution, the proclivity towards monarchy was anything but absent. Following the signing of the Declaration of Independence in 1776, a letter was published in Philadelphia stating: ‘The genius of the Americans is of a monarchical spirit; this is natural from the government they have ever lived under. It is therefore impossible to found a simple Republic in America. Another reason that operates strongly against such a government is the great distinctions of person, and difference in their estates or property, which co-operates strongly with the genius of the people in favor of monarchy.’ Interestingly, the accusation of being monarchical was used by the Federalists against the anti-federalist Republicans; however, it would not be far off the mark to turn that accusation around and apply it to the Federalists themselves, specifically Alexander Hamilton, who viewed republicanism as a stop-gap of sorts before American monarchism was ready to become established. The reason why this never happened is because there was never the formation of a cohesively visible aggregation of American monarchists (composed largely of educated soldiers) who pressured openly for the total centralization of political power into a new line of royalty to which they would pledge their undying allegiance.”

Federalist No. 26, Hamilton:

- “It was a thing hardly to be expected that in a popular revolution the minds of men should stop at that happy mean which marks the salutary boundary between power and privilege, and combines the energy of government with the security of private rights. A failure in this delicate and important point is the great source of the inconveniences we experience, and if we are not cautious to avoid a repetition of the error, in our future attempts to rectify and ameliorate our system, we may travel from one chimerical project to another; we may try change after change; but we shall never be likely to make any material change for the better.”

Absence of government would easily remove any notions of power and privilege and simultaneously keep intact the private freedoms of the otherwise ‘governed.’ In this way, anarchism is preferable to the false dichotomy between “freedom” and “security” arbitrarily held within the maw of Leviathan.

- “The opponents of the proposed Constitution combat, in this respect, the general decision of America; and instead of being taught by experience the propriety of correcting any extremes into which we may have heretofore run, they appear disposed to conduct us into others still more dangerous, and more extravagant. As if the tone of government had been found too high, or too rigid, the doctrines they teach are calculated to induce us to depress or to relax it, by expedients which, upon other occasions, have been condemned or forborne. It may be affirmed without the imputation of invective, that if the principles they inculcate, on various points, could so far obtain as to become the popular creed, they would utterly unfit the people of this country for any species of government whatever. But a danger of this kind is not to be apprehended. The citizens of America have too much discernment to be argued into anarchy.”

Hamilton makes the Federalist’s proposed Constitution sound like an innocent document, rather than affirming the abusive powers of the State held in consensus by the signatories thereof.

- “And I am much mistaken, if experience has not wrought a deep and solemn conviction in the public mind, that greater energy of government is essential to the welfare and prosperity of the community.”

As far as I’m concerned the welfare and prosperity of a community doesn’t necessitate the existence of government.

- “Let us examine whether there be any comparison, in point of efficacy, between the provision alluded to and that which is contained in the new Constitution, for restraining the appropriations of money for military purposes to the period of two years. The former, by aiming at too much, is calculated to effect nothing; the latter, by steering clear of an imprudent extreme, and by being perfectly compatible with a proper provision for the exigencies of the nation, will have a salutary and powerful operation.”

Indeed, let us examine the Federalist’s new Constitution’s Army Clause. Article, Section 8, Clause 12 says: ‘The Congress shall have the power to raise and support armies, but no appropriation of money to that use shall be for a longer term than two years.’

Article 9 of the Articles of Confederation states (regarding the subjects of a ‘military’ and ‘army’):

” The United States in Congress assembled shall never engage in a war, nor grant letters of marque or reprisal in time of peace, nor enter into any treaties or alliances, nor coin money, nor regulate the value thereof, nor ascertain the sums and expenses necessary for the defense and welfare of the United States, or any of them, nor emit bills, nor borrow money on the credit of the United States, nor appropriate money, nor agree upon the number of vessels of war, to be built or purchased, or the number of land or sea forces to be raised, nor appoint a commander in chief of the army or navy, unless nine States assent to the same: nor shall a question on any other point, except for adjourning from day to day be determined, unless by the votes of the majority of the United States in Congress assembled. The Congress of the United States shall have power to adjourn to any time within the year, and to any place within the United States, so that no period of adjournment be for a longer duration than the space of six months, and shall publish the journal of their proceedings monthly, except such parts thereof relating to treaties, alliances or military operations, as in their judgement require secrecy; and the yeas and nays of the delegates of each State on any question shall be entered on the journal, when it is desired by any delegates of a State, or any of them, at his or their request shall be furnished with a transcript of the said journal, except such parts as are above excepted, to lay before the legislatures of the several States.”

One of the earliest violations of the new Constitution’s Army Clause was the Westward Expansion, which lasted a total of 45 years (1815-1860). That’s well beyond the two-year limit. For a comparison, the indefinite “War on Terror” (2001-?) beginning operations in Afghanistan also remains in violation of the Army Clause’s two year limit on the Army. Instead of ending armed forces exertion in foreign lands, they were instead deployed into a new war zone, Iraq, three years later.

- “Independent of parties in the national legislature itself, as often as the period of discussion arrived, the State legislatures, who will always be not only vigilant but suspicious and jealous guardians of the rights of the citizens against encroachments from the federal government, will constantly have their attention awake to the conduct of the national rulers, and will be ready enough, if anything improper appears, to sound the alarm to the people, and not only to be the voice, but, if necessary, the arm of their discontent.”

Had there been no desire by conspiring entities who wanted a monopoly on force to begin with, there’d be no need for citizens to concern themselves with the natural tendencies of rulers to do as they please, even if it brings harm and ‘discontent’ to the citizens themselves. Imagine how much simpler, the absence of a monopolistic legislature, would provide, to the sleeping American giant.

- “An army, so large as seriously to menace those liberties, could only be formed by progressive augmentations; which would suppose, not merely a temporary combination between the legislature and executive, but a continued conspiracy for a series of time. Is it probable that such a combination would exist at all? Is it probable that it would be persevered in, and transmitted along through all the successive variations in a representative body, which biennial elections would naturally produce in both houses? Is it presumable, that every man, the instant he took his seat in the national Senate or House of Representatives, would commence a traitor to his constituents and to his country? Can it be supposed that there would not be found one man, discerning enough to detect so atrocious a conspiracy, or bold or honest enough to apprise his constituents of their danger? If such presumptions can fairly be made, there ought at once to be an end of all delegated authority. The people should resolve to recall all the powers they have heretofore parted with out of their own hands, and to divide themselves into as many States as there are counties, in order that they may be able to manage their own concerns in person.”

I’m so confused. Hamilton is suggesting, as an answer to a standing army within The States, that the best way to resolve this issue for ‘the people’ is to balkanize themselves into their own mini-States or secessionist colonies. Seems he wants to have his cake on insurrection (Article 1, Sec. 8. Clause 15 of the Federalist’s Constitution) and eat it too, while simultaneously advising the very insurrection that would later be criminalized under the U.S. Constitution of 1787. I’m just at a loss for words on this. It’s hypocritical appeasement to his readership. If ever there was an early example of politicians working behind the backs of the public, to serve their own selfish interests, the Federalists qualify with great ease in the Papers from everything I’ve read thus far.

- “Few persons will be so visionary as seriously to contend that military forces ought not to be raised to quell a rebellion or resist an invasion; and if the defense of the community under such circumstances should make it necessary to have an army so numerous as to hazard its liberty, this is one of those calamities for which there is neither preventative nor cure. It cannot be provided against by any possible form of government; it might even result from a simple league offensive and defensive, if it should ever be necessary for the confederates or allies to form an army for common defense.”

It appears Hamilton and company make no contention about the hazardous nature to liberty that exceptions for the standing army provisions provide in their proposed Constitution. The problem in the argument presented by Hamilton is that “common defense” must be consolidated into government into the first place, we’ve encountered similar problems before regarding ‘national defense’ via naval capabilities in previous Papers. Besides, I don’t feel it’s in the spirit of “common defense” that wars of aggression are launched against countries considered demonstrably weak, easily exploitable to political bribes, and other nonsense. Had the oh-so-wonderful Federalists found any foresight in the dangerous model of government they sought to coercively implement, they’d need reason to desist from imposing such a future on the governed of The States as we know them.

- “But it is an evil infinitely less likely to attend us in a united than in a disunited state; nay, it may be safely asserted that it is an evil altogether unlikely to attend us in the latter situation.”

What isn’t said by Hamilton, is that the cost of this “unity” is coercion and outright violence for those who “disobey” the command to join the collectivist whole. Yes, evil indeed.

- “But in a state of disunion (as has been fully shown in another place), the contrary of this supposition would become not only probable, but almost unavoidable.”

A ‘state of disunion’ would be people exercising their liberty. Can’t be having none of that. Can we, Mr. Hamilton?

Federalist No. 27, Hamilton:

- “It has been urged, in different shapes, that a Constitution of the kind proposed by the convention cannot operate without the aid of a military force to execute its laws. This, however, like most other things that have been alleged on that side, rests on mere general assertion, unsupported by any precise or intelligible designation of the reasons upon which it is founded.”

Well, he’s not entirely wrong. Instead of policing powers being granted to military forces, instead they are vested in police that serve the monopoly on violence instead. These same police entities would become militarized in the execution of laws, making them almost entirely indistinguishable from a militant standing army. A convenient loophole for the Federal government, and I’m sure the Federalists wouldn’t have minded much.

- “Various reasons have been suggested, in the course of these papers, to induce a probability that the general government will be better administered than the particular governments; the principal of which reasons are that the extension of the spheres of election will present a greater option, or latitude of choice, to the people; that through the medium of the State legislatures which are select bodies of men, and which are to appoint the members of the national Senate there is reason to expect that this branch will generally be composed with peculiar care and judgment; that these circumstances promise greater knowledge and more extensive information in the national councils, and that they will be less apt to be tainted by the spirit of faction, and more out of the reach of those occasional ill-humors, or temporary prejudices and propensities, which, in smaller societies, frequently contaminate the public councils, beget injustice and oppression of a part of the community, and engender schemes which, though they gratify a momentary inclination or desire, terminate in general distress, dissatisfaction, and disgust.”

As far as I’ve been able to determine, ‘general’ and ‘particular’ governments, elections, legislatures, Senators, national councils are all composed of the ill-fettered nature of the rabid dog called The State. Neither localized nor distant governance is angelic compared to each other. It’s a childish ascertation to believe otherwise. Damn your chimera, Mr. Hamilton!

- “It will be sufficient here to remark, that until satisfactory reasons can be assigned to justify an opinion, that the federal government is likely to be administered in such a manner as to render it odious or contemptible to the people, there can be no reasonable foundation for the supposition that the laws of the Union will meet with any greater obstruction from them, or will stand in need of any other methods to enforce their execution, than the laws of the particular members.”

A contemptible government is worthless, the very thought that it’s greedily proposed with the ‘laws of the Union’ by Hamilton says quite a lot about his character. It’s not a very pretty image, for those with eyes to see.

- “The hope of impunity is a strong incitement to sedition; the dread of punishment, a proportionably strong discouragement to it.”

Of course, the people are allowed to be abolish the State BUT they must somehow do it without ‘seditious’ acts, because the dread of punishment is criminalization. I’m going to guess the answer to that conundrum will never be found throughout the Federalist Papers themselves.

- “A government continually at a distance and out of sight can hardly be expected to interest the sensations of the people. The inference is, that the authority of the Union, and the affections of the citizens towards it, will be strengthened, rather than weakened, by its extension to what are called matters of internal concern; and will have less occasion to recur to force, in proportion to the familiarity and comprehensiveness of its agency. The more it circulates through those channels and currents in which the passions of mankind naturally flow, the less will it require the aid of the violent and perilous expedients of compulsion.”

I guess that’s what all the unquestioning flag worshiping nonsense is all about. Sedate the minds of resistance into mandatory, ‘lawful’, acts of tedious exercise like the Pledge of Allegiance. Pathetic.

- “It has been shown that in such a Confederacy there can be no sanction for the laws but force; that frequent delinquencies in the members are the natural offspring of the very frame of the government; and that as often as these happen, they can only be redressed, if at all, by war and violence.”

Because the Union would NEVER (read: did and has) maintained sanctions for laws by violence. I recommend to readers of the Federalist Papers, often you are required to read between the lines to understand what ISN’T present and thus deserves commentary.

- “It is easy to perceive that this will tend to destroy, in the common apprehension, all distinction between the sources from which they might proceed; and will give the federal government the same advantage for securing a due obedience to its authority which is enjoyed by the government of each State, in addition to the influence on public opinion which will result from the important consideration of its having power to call to its assistance and support the resources of the whole Union.”

Finally, some honesty. Government is most certainly about obedience to authoritarianism.

- “The legislatures, courts, and magistrates, of the respective members, will be incorporated into the operations of the national government as far as its just and constitutional authority extends; and will be rendered auxiliary to the enforcement of its laws.”

Here we see, through Hamilton’s words that it’s NOT that the Federalist’s were jealous of the Confederate State’s exercising their standing army ‘Constitutional’ provisions, although the hypocrisy is notable, they were jealous and wanted to share that authoritarian power under the coercive banner of the Union. There’s “Constitutional” government in action for you. Still like it, minarchists? I sure as hell don’t.

Federalist No. 28, Hamilton:

- “Our own experience has corroborated the lessons taught by the examples of other nations; that emergencies of this sort will sometimes arise in all societies, however constituted; that seditions and insurrections are, unhappily, maladies as inseparable from the body politic as tumors and eruptions from the natural body; that the idea of governing at all times by the simple force of law (which we have been told is the only admissible principle of republican government), has no place but in the reveries of those political doctors whose sagacity disdains the admonitions of experimental instruction.”

How government chooses to handle the subject of ‘sedition’ can turn the very notion of Republicanism on its head. Instead of being a bottom-up force of the governed, it’s a top-down act of state terrorism through technocratic control of American society, as envision in quotations below by Zbigniew Brzezinski.

Perhaps one of the best examples of this mentality I could find is a complaint by members of the Trilateral Commission that American’s were being “too democratic” (bottom-up) as described by Samuel Huntington:

“The 1960s also saw, of course, a marked upswing in other forms of citizen participation, in the form of marches, demonstrations, protest movements, and “cause organizations (such as Common Cause, Nader groups, and environmental groups). In a related and similar fashion, the 1960s also saw a reassertion of the primary of equality as a goal in social, economic, and political life. During the mid-1960s, at the peak of the democratic surge and of the Vietnam War, public opinion on these issues changed dramatically. When asked in 1960, for instance, how they felt about current defense spending, 18 percent of the public said the United States was spending too much on defense, 21 percent said too little, and 45 percent said the existing level was about right. Nine years later, in July 1969, the proportion of the public saying that too much was being spend on defense had dropped from 21 percent to 8 percent and the proportion approving the current level had declined from 45 percent to 31 percent. The essence of the democratic surge of the 1960s was a general challenge to existing systems of authority, public and private. People no longer felt the same compulsion to obey those whom they had previously considered superior to themselves in age, rank, status, expertise, character, or talents. Authority, based on hierarchy, expertise, and wealth all, obviously, ran counter to the democratic and egalitarian temper of the times, and during the 1960s, all three came under heavy attack. The polarization was clearly related to the nature of the issues which became the central items on the political agenda of the mid-1960s. The three major clusters of issues which then came to the fore were: social issues, such as use of drugs, civil liberties, and role of women; racial issues, involving integration, busing, government aid to minority groups, and urban riots; military issues, involving primarily, of course, the war in Vietnam but also the draft, military spending, military aid programs, and the role of the military-industrial complex more generally. Not only was there a decline in the confidence of the public in political leaders, but there was also a marked decline in the confidence of political leaders in themselves. In addition, and probably more importantly, political leaders also had doubts about the morality of their rule. They too shared in the democratic, participatory, and egalitarian ethos of the time, and hence had questions about the legitimacy of hierarchy, coercion, discipline, secrecy, and deception – all of which are, in some measure, inescapable attributes of the process of government. Probably no development of the 1960s and 1970s has greater import for the future of American politics than the decline of the authority, status, influence, and effectiveness of the presidency. Some of the problems of governance in the United States today stem from an excess of democracy – an ‘excess in democracy’ in much the same sense in which David Donald used the term to refer to the consequences of the Jacksonian revolution which helped to precipitate the Civil War. Needed, instead, is a greater degree of moderation in democracy. The effective operation of a democratic political system usually requires some measure of apathy and noninvolvement on the part of some individuals and groups. In the past, every democratic society has had a marginal population, of greater or lesser size, which has not actively participated in politics. In itself, the marginality on the part of some groups in inherently undemocratic, but it has also been one of the factors which has enabled democracy to function effectively. Marginal social groups, as in the case of the blacks, are now becoming full participants in the political system. Yet, the danger of overloading the political system with demands which extend its functions and undermine its authority still remains. The vulnerability of democratic government in the United States thus comes not primarily from external threats, though such threats are real, nor from internal subversion from the left or the right, although both possibilities could exist, but rather from the internal dynamics of democracy itself in a highly educated, mobilized, and participant society. We have come to recognize that there are potentially desirable limits to economic growth. There are also potentially desirable limits to the indefinite extension of political democracy. Democracy will have a longer life if it has a more balanced existence.” -Michel J. Crozier, Samuel P. Huntington and Joji Watanuki, The Crisis of Democracy. (Report on the Governability of Democracies to the Trilateral Commission, New York University Press, 1975), pgs 61, 62, 71, 74-75, 77, 93, 113-114, 115.

Zbigniew Brzezinski’s ‘answer’ is the technocratic society in a top-down response: “A society that is shaped culturally, psychologically, socially, and economically by the impact of technology and electronics – particularly in the arena of computers and communications. The industrial process is no longer the principal determinant of social change, altering the mores, the social structure, and the values of society. The traditionally democratic American society could, because of its fascination with technical efficiency, become an extremely controlled society, and its humane and individualistic qualities would thereby be lost.”-Zbigniew Brzezinski, Between Two Ages: America’s Role in the Technetronic Era. (Viking Press, New York, 1970).

- “An insurrection, whatever may be its immediate cause, eventually endangers all government. Regard to the public peace, if not to the rights of the Union, would engage the citizens to whom the contagion had not communicated itself to oppose the insurgents; and if the general government should be found in practice conducive to the prosperity and felicity of the people, it were irrational to believe that they would be disinclined to its support.”

Insurrection is considered competition to the monopoly on violence, thus, all responses to it must be done under the category of ‘keeping the peace.’ Where does Hamilton suppose the ‘insurgents’ come from, if not the people that are tired of the government itself? You know, the people he recognized in a previous Paper as having the power to given (and therefore) revoke their ‘consent of the governed’. Lots of hypocrisy here.

- “If, on the contrary, the insurrection should pervade a whole State, or a principal part of it, the employment of a different kind of force might become unavoidable.”

Of course. Gotta secure that monopoly on violence by all means necessary.

- “Is it not surprising that men who declare an attachment to the Union in the abstract, should urge as an objection to the proposed Constitution what applies with tenfold weight to the plan for which they contend; and what, as far as it has any foundation in truth, is an inevitable consequence of civil society upon an enlarged scale? Who would not prefer that possibility to the unceasing agitations and frequent revolutions which are the continual scourges of petty republics?”

Sometimes Hamilton would like America to be a Republic, other times, he thinks not. I wouldn’t expect any less inconsistency from an aristocratic doppelganger who deceives the public in the name of coercively implementing a “new government” and “new Constitution” whether the governed at the time desired such or not.

- “Whether we have one government for all the States, or different governments for different parcels of them, or even if there should be an entire separation of the States, there might sometimes be a necessity to make use of a force constituted differently from the militia, to preserve the peace of the community and to maintain the just authority of the laws against those violent invasions of them which amount to insurrections and rebellions.”

I find it astoundingly hypocritical that rebellion against foreign governments interfering in domestic matters of The States is a rallying cry for the federal government, but any notions that the governed don’t wish to be under the iron heel of local authoritarians is criminalized as an unconsciousable act. The Federalists are certainly hypocritical politicians of their time. The message becomes thus: ‘You are permitted to rebel against any other government on the planet, but NEVER the government that coercively ‘allowed’ you to live under its jurisdiction. You must accept that coercion and be patriotically thankful for it.’

- “If the representatives of the people betray their constituents, there is then no resource left but in the exertion of that original right of self-defense which is paramount to all positive forms of government, and which against the usurpations of the national rulers, may be exerted with infinitely better prospect of success than against those of the rulers of an individual state.”

I’m so confused right now. Is insurrection a natural right of the people or not, Mr. Hamilton? You can’t say you want people to exercise their right to self-defense or abolishing the State, then literally in the next (or previous) breath insist that such exercising of abolishment of the State must be criminalized.

- “It may safely be received as an axiom in our political system, that the State governments will, in all possible contingencies, afford complete security against invasions of the public liberty by the national authority.”

Anyone who trusts ANY governments with the security of their liberty is supremely naive.

- “When will the time arrive that the federal government can raise and maintain an army capable of erecting a despotism over the great body of the people of an immense empire, who are in a situation, through the medium of their State governments, to take measures for their own defense, with all the celerity, regularity, and system of independent nations? The apprehension may be considered as a disease, for which there can be found no cure in the resources of argument and reasoning.”

There is absolutely no reasoning with Hamilton throughout these Papers, he talks out of both sides of his mouth on the subject of insurrection.

Federalist No. 29, Hamilton:

- “The power of regulating the militia, and of commanding its services in times of insurrection and invasion are natural incidents to the duties of superintending the common defense, and of watching over the internal peace of the Confederacy.”

I can only guess where Hamilton is taking this starting sentence off. Previously he made the case of jealousy that the Confederacy wouldn’t share its standing army powers against ‘insurrection’ with the Union.

- “Of the different grounds which have been taken in opposition to the plan of the convention, there is none that was so little to have been expected, or is so untenable in itself, as the one from which this particular provision has been attacked.”

Many of the proposed provisions in the Federalist’s Constitution deserved to be “attacked”. Notions of tackling insurrection, without even defining it, deserve absolute vehement opposition by anyone that consistently cares for liberty.

- “If a well-regulated militia be the most natural defense of a free country, it ought certainly to be under the regulation and at the disposal of that body which is constituted the guardian of the national security.”

A state monopoly on violence wants a regulated armed force in the name of…freedom..for the country upon which it governs, in the name of ‘national security.’ Right. That makes my skin crawl.

- “In order to cast an odium upon the power of calling forth the militia to execute the laws of the Union, it has been remarked that there is nowhere any provision in the proposed Constitution for calling out the posse comitatus, to assist the magistrate in the execution of his duty, whence it has been inferred, that military force was intended to be his only auxiliary.”

Posse Comitatus isn’t all it’s cracked up to be.

- “It would be as absurd to doubt, that a right to pass all laws necessary and proper to execute its declared powers, would include that of requiring the assistance of the citizens to the officers who may be entrusted with the execution of those laws, as it would be to believe, that a right to enact laws necessary and proper for the imposition and collection of taxes would involve that of varying the rules of descent and of the alienation of landed property, or of abolishing the trial by jury in cases relating to it.”

And the penalties faced by citizens who don’t wish to assist in the monopoly on violence is?

- “How the national legislature may reason on the point, is a thing which neither they nor I can foresee.”

Because if a legislature exists, obviously nothing could possibly go wrong on the subject of militias, or even the previous subject, insurrections.

- “In reading many of the publications against the Constitution, a man is apt to imagine that he is perusing some ill written tale or romance, which instead of natural and agreeable images, exhibits to the mind nothing but frightful and distorted shapes “Gorgons, hydras, and chimeras dire’’; discoloring and disfiguring whatever it represents, and transforming everything it touches into a monster.”

I’d argue these publications weren’t far off in warning about the dangerous superstition of The State. It’s a monstrosity that loves breeding imitations of itself in the minds of unquestioning adherents.

- “Are suppositions of this sort the sober admonitions of discerning patriots to a discerning people? Or are they the inflammatory ravings of incendiaries or distempered enthusiasts? If we were even to suppose the national rulers actuated by the most ungovernable ambition, it is impossible to believe that they would employ such preposterous means to accomplish their designs.”

This language from one Mr. Hamilton, from the very onset of the Papers, sought to coercively demand a ‘new government’ and ‘new Constitution’ be formed. Oh, sweet irony.

- “In times of insurrection, or invasion, it would be natural and proper that the militia of a neighboring State should be marched into another, to resist a common enemy, or to guard the republic against the violence of faction or sedition.”

Who defines insurrection and sedition? The very man who propagates the notion that his “proposed Constitution” can do no wrong. The freedom umbrella has better answers to this miserable jigsaw puzzle of Statism on these subjects.

Federalist No. 30, Hamilton:

- “There must be interwoven, in the frame of the government, a general power of taxation, in one shape or another.”

Always beware when Hamilton says “MUST”, what follows provides little comfort.

- “One of two evils must ensue; either the people must be subjected to continual plunder, as a substitute for a more eligible mode of supplying the public wants, or the government must sink into a fatal atrophy, and, in a short course of time, perish.”

I’m quite alright with Leviathan perishing.